|

The Julian and Gregorian Calendarsby Peter Meyer |

|

The Julian and Gregorian Calendarsby Peter Meyer |

Originally the Romans numbered years ab urbe condita, that is, "from the founding of the city" (of Rome, where much of the character of the modern world had its beginnings). Had this old calendar remained in use, 1996-01-14 would have been New Year's Day in the year 2749 a.u.c. (In this article dates are often given in IS0 8601 format.)

Following his conquest of Egypt in 48 B.C. Julius Caesar consulted the Alexandrian astronomer Sosigenes about calendar reform (since the a.u.c. calendar then used by the Romans was completely inadequate to the needs of the emerging empire, which Caesar was poised to command, briefly as it turned out). The calendar which Julius Caesar adopted in the year 709 a.u.c. (what we now call 46 B.C.) was identical to the Alexandrian Aristarchus' calendar of 239 B.C., and consisted of a solar year of twelve months and of 365 days with an extra day every fourth year. It is unclear as to where or how Aristarchus arrived at this calendar, but one may speculate that Babylonian science was involved.

As we can read in the excellent article, "The Western Calendar and Calendar Reforms" in the Encyclopedia Brittanica, Sosigenes decided that the year known in modern times as 46 B.C. should have two intercalations. The first was the customary intercalation of 23 days following February 23, the second, "to bring the calendar in step with the equinoxes, was achieved by inserting two additional months between the end of November and the beginning of December. This insertion amounted to an addition of 67 days, making a year of no less than 445 days and causing the beginning of March, 45 B.C. in the Roman republican calendar, to fall on what is still called January 1 of the Julian Calendar."

According to Kevin Tobin Julius Caesar wanted to start the year on the vernal equinox or the winter solstice, but the Senate, which traditionally took office on January 1st, the start of the Roman civil calendar year, wanted to keep January 1st as the start of the year, and Caesar yielded in a political compromise.

The Roman date-keepers initially misunderstood Caesar's instructions concerning the new calendar (according to Macrobius), and erroneously took every third year, rather than every fourth year, to be a leap year. There is some dispute as to exactly which years from 43 B.C. through to 8 A.D. were actually leap years, but a reconstruction which is consistent with the available evidence is that every third year following 43 B.C. (i.e. 40 B.C., 37 B.C., etc.) was a leap year, until 10 B.C., after which, according to this hypothesis, Augustus Caesar (Julius Caesar's successor) suspended leap years, reinstating them with the leap year of 4 A.D.

Another source of uncertainty regarding exact dating of days at this time derives from changes made by Augustus to the lengths of the months. According to some accounts, originally the month of February had 29 days and in leap years 30 days (unlike 28 and 29 now). It lost a day because at some point the fifth and six months of the old Roman calendar were renamed as Julius and Augustus respectively, in honor of their eponyms, and the number of days in August, previously 30, now became 31 (the same as the number of days in July), so that Augustus Caesar would not be regarded as inferior to Julius Caesar. The extra day needed for August was taken from the end of February. However there is still no certainty regarding these matters, so all dates prior to A.D. 4, when the Julian Calendar finally stabilized, are uncertain.

Subsequently the Julian Calendar became widespread as a result of its use throughout the Roman Empire and later by various Christian churches, which inherited many of the institutions of the Roman world.

The system of numbering years A.D. (for "Anno Domini") was instituted in about the year 527 A.D. by the Roman abbot Dionysius Exiguus, who reckoned that the Incarnation of Jesus had occurred on March 25 in the year 754 a.u.c., with his birth occurring nine months later. Thus the year 754 a.u.c. was designated by him as the year 1 A.D. It is generally thought that his estimate of the time of this event was off by a few years (and there is even uncertainty as to whether he identified 1 A.D. with 754 a.u.c. or 753 a.u.c.).

The question has been raised as to whether the first Christian millennium should be counted from 1 A.D. or from the year preceding it. According to Dionysius the Incarnation occurred on March 25th of the year preceding 1 A.D. (with the birth of Jesus occurring nine months later on December 25th), so it is reasonable to regard that year, rather than 1 A.D. as the first year of the Christian Era. In that case 1 A.D. is the second year, and 999 A.D. is the 1000th year, of the first Christian millennium, implying that 1999 A.D. is the final year of the second Christian millennium and 2000 A.D. the first year of the third.

Whatever, this error accumulates so that after about 131 years the calendar is out of sync with the equinoxes and solstices by one day. Thus as the centuries passed the Julian Calendar became increasingly inaccurate with respect to the seasons. This was especially troubling to the Roman Catholic Church because it affected the determination of the date of Easter, which, by the 16th Century, was well on the way to slipping into summer.

Whatever, this error accumulates so that after about 131 years the calendar is out of sync with the equinoxes and solstices by one day. Thus as the centuries passed the Julian Calendar became increasingly inaccurate with respect to the seasons. This was especially troubling to the Roman Catholic Church because it affected the determination of the date of Easter, which, by the 16th Century, was well on the way to slipping into summer.

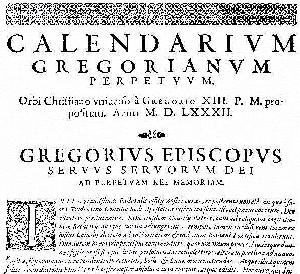

Pope Paul III recruited several astronomers, principally the Jesuit Christopher Clavius (1537-1612), to come up with a solution. They built upon calendar reform proposals by the astronomer and physician Luigi Lilio (d. 1576). When Pope Gregory XIII was elected he found various proposals for calendar reform before him, and decided in favor of that of Clavius. On 1582-02-24 he issued a papal bull, Inter Gravissimas, establishing what is now called the Gregorian Calendar reform. (The full text may be read in both the Latin original and a French translation by Rudolphe Audette, and in an English translation done by Bill Spencer.)

The Gregorian reform consisted of the following:

According to some, the term "leap year" derives from the fact that the day of the week on which certain festivals were held normally advanced by one day (since 365 = 7*52 + 1), but in years with an extra day the festivals would "leap" to the weekday following that. However, it may be derived from an old Norwegian word "hlaupâr" which entered the English language at the time of the Viking invasions (8th - 10th Centuries).

In his excellent book Marking Time Duncan Steel remarks (p.165) that it is often claimed that part of the Gregorian reform consisted in setting the first day of the year (New Year's Day) to January 1st, but that in fact the papal bull made no reference to the date of New Year's Day. January 1st was already New Year's Day in many European countries. The ecclesiastical New Year coincided with Christmas Day until it was changed to January 1st by Pope Pius X in 1910 (coming into effect in 1911).

It may be noted that there was no necessity for ten days, rather than, say, twelve days to have been omitted from the calendar. In fact, the calendar could have been reformed without omitting any days at all, since only the new rule for leap years is required to keep the calendar synchronized with the vernal equinox. The number of days omitted determines the date for the vernal equinox, an omission of ten days resulting in a date usually of March 20th.

The vernal equinox year during the last 2000 years is 365.2424 days. The average length of the Julian year (365.25 days) differs from this value by 0.0076 days. So from the year 1 to the year 1582 the calendar drifted off the vernal equinox year by 1581*0.0076 = 12.02 days. Why didn't Pope Gregory remove twelve days, instead of just ten? It has to do with the First Council of Nicaea, which was held in Nicaea (now Iznik, Turkey) in the year 325 A.D. One of the matters settled by this council was the method for determining the date of Easter (which should occur around the vernal equinox), so as to make it independent of the Jewish Calendar. From the year 325 to the year 1582 the calendar diverged (from the vernal equinox) by 1257*0.0076 = 9.55 days, so ten days were removed in an attempt to restore the date of the vernal equinox to (about) the same date of the year at which it had occurred at the time of the Council of Nicaea.

The matter is not this simple, however, because the date of the vernal equinox in the calendar of the Roman Catholic Church as established by the Council of Nicaea (in 325 A.D.) is March 21, but the effect of removing ten days in 1582 had the result that the vernal equinox occurs in the Gregorian Calendar mostly on March 20, less often on March 21, sometimes on March 19 and sometimes even on March 22 according to local time in the Far East. So should Pope Gregory have omitted nine days? Or perhaps eleven? Presumably Pope Gregory's astronomical advisors considered all three possibilities. Some say that the choice of ten was a compromise, supported by the fact that the omission of ten days made it easier to correct old calendars simply by the insertion of an "X" (the Latin numeral for "10").

In fact a non-Gregorian calendar reform (involving a 33-year cycle and a prime meridian running through Virginia) would have stabilized the vernal equinox at March 21 for the whole world (as Simon Cassidy has shown). Whether Pope Gregory's advisors were aware of this reform option is not known for sure.

In many countries the Julian Calendar was used by the general population long after the official introduction of the Gregorian Calendar. Thus events were recorded in the 16th to 18th Centuries with various dates, depending on which calendar was used. Dates recorded in the Julian Calendar were marked "O.S." for "Old Style", and those in the Gregorian Calendar were marked "N.S." for "New Style".

To complicate matters further New Year's Day, the first day of the new year, was celebrated in different countries, and sometimes by different groups of people within the same country, on either January 1, March 1, March 25 or December 25. January 1 seems to have been the usual date but there was no standard observed. With the introduction of the Gregorian Calendar in Britain and the colonies New Year's Day was generally observed on January 1. Previously in the colonies it was common for March 24 of one year to be followed by March 25 of the next year. This explains why, with the calendrical reform and the shift of New Year's Day from March 25 back to January 1, the year of George Washington's birth changed from 1731 to 1732. In the Julian Calendar his birthdate is 1731-02-11 but in the Gregorian Calendar it is 1732-02-22.

Sweden adopted the Gregorian Calendar in 1753, Japan in 1873, Egypt in 1875, Eastern Europe during 1912 to 1919 and Turkey in 1927. Following the Bolshevik Revolution in Russia it was decreed that thirteen days would be omitted from the calendar, the day following January 31, 1918, O.S. becoming February 14, 1918, N.S. (Further information can be found in The Perpetual Calendar and here.)

In 1923 the Eastern Orthodox Churches adopted a modified form of the Gregorian Calendar in an attempt to render the calendar more accurate (see below). October 1, 1923, in the Julian Calendar became October 14, 1923, in the Eastern Orthodox calendar. The date of Easter is determined by reference to modern lunar astronomy (in contrast to the more approximate lunar model of the Gregorian system).

The Gregorian Calendar is the calendar which is currently in use in all European and European-influenced countries, and Dionysius Exiguus's system of numbering years A.D. has endured to the present time.

The abbreviation A.D. is short for "Anni Domini Nostri Jesu Christi", i.e., "in the year of Our Lord Jesus Christ". Since Muslims, Jews, etc., may not be entirely comfortable with this, the designation "A.D." is now sometimes replaced by the more neutral C.E. (for "Common Era"), and instead of B.C. ("Before Christ") B.C.E. (for "Before Common Era") is sometimes used.

| 1 A.D. = 1 C.E. = year 1 |

| 1 B.C. = 1 B.C.E. = year 0 |

| 2 B.C. = 2 B.C.E. = year -1 and so on |

More generally, a year popularly designated n B.C. or n B.C.E. is designated by astronomers as the year -(n-1).

The rules for leap years work for years prior to 1 C.E. only if those years are expressed according to the astronomical system, not if expressed as years B.C.E. 4 C.E. is a leap year in both calendars, 1 B.C.E. = astronomical year 0, 5 B.C.E. = year -4, 9 B.C.E. = year -8, and so on, are all leap years. 101 B.C.E. = year -100 is a leap year in the (proleptic) Julian Calendar but not in the (proleptic) Gregorian Calendar. These statements, however, are only theoretically true, because (as noted above) prior to 4 C.E. the leap years were not observed correctly by the Roman calendrical authorities.

The choice of which system of numbering years to use is relevant to the question: When Does the New Millennium Begin? as can be seen from the following:

Gregorian Religiously Common Era

Calendar Neutral Calendar

3 BC 3 BCE -2 CE

2 BC 2 BCE -1 CE

CE millennium begins 0-01-01 CE

1 BC 1 BCE 0 CE

Gregorian millennium usually taken to begin 1-1-1 AD

1 AD 1 CE 1 CE

2 AD 2 CE 2 CE

... ... ...

1998 AD 1998 CE 1998 CE

1999 AD 1999 CE 1999 CE

CE millennium ends 1999-12-31 CE

CE millennium begins 2000-01-01 CE

2000 AD 2000 CE 2000 CE

Gregorian millennium usually taken to end 2000-12-31 AD

Gregorian millennium usually taken to begin 2001-1-1 AD

2001 AD 2001 CE 2001 CE |

January 1st, 1 AD is usually taken to be the start of the first Christian millennium, but a case could be made for January 1st, 1 BC (see the comment above concerning the Incarnation), which would imply that the third Christian millennium began on January 1st, 2000 AD.

We can, however, identify particular days prior to October 15, 1582 (Gregorian), by means of dates in the Gregorian Calendar simply by projecting the Gregorian dating system back beyond the time of its implementation. A calendar obtained by extension earlier in time than its invention or implementation is called the "proleptic" version of the calendar, and thus we obtain the proleptic Gregorian Calendar. The Julian Calendar also can be extended backward as the proleptic Julian Calendar.

For example, even though the Gregorian Calendar was implemented on October 15, 1582 (Gregorian) we can still say that the date of the day one year before was October 15, 1581 (Gregorian), even though people alive on that day would have said that the date was October 5, 1581 (the Julian date at that time).

Similarly, dates after October 15, 1582 (Gregorian) have equivalent, but different, dates in the Julian Calendar. For example, the first version of this article was completed on 1992-10-10 in the Gregorian Calendar, but it is also true to say that it was completed on 1992-09-27 in the Julian Calendar. As another example, the date of the winter solstice in the year 2012 is 2012-12-21 (Gregorian), which is 2012-12-08 (Julian).

Thus any day in the history of the Earth, either in the past or in the future, can be specified as a date in either of these two calendrical systems. The dates will generally be different; in fact they will be the same only for dates from March 1st, 200, to February 28, 300. The dates in neither calendar will coincide with the seasons in the distant past or distant future, but that does not affect the validity of these calendars as systems for uniquely identifying particular days.

See also a note I sent to the CALNDR-L mailing list Re: Proleptic calendar conventions.

For conversion between Julian and Gregorian dates see Julian-Gregorian- Dee Date Calculator.

Year Length of tropical year in days

-5000 365.24253

-4000 365.24250

-3000 365.24246

-2000 365.24242

-1000 365.24237

0 365.24231

1000 365.24225

2000 365.24219

3000 365.24213

4000 365.24207

5000 365.24201

|

Thus the value of the tropical year varies over this 10,000-year timespan by as much as .00052 days (about 45 seconds).

Whereas in the Gregorian Calendar a century year is a leap year only if division of the century number by 4 leaves a remainder of 0, in the Eastern Orthodox system a century year is a leap year only if division of the century number by 9 leaves a remainder of 2 or 6. This implies an average calendar year length in the Orthodox Calendar of 365.24222 days. This is very close to the present mean solar value of 365.24219, and the Eastern Orthodox Calendar is at present significantly more accurate in this respect than the Gregorian. Were the mean solar year to remain constant, the Orthodox Calendar would be off by one day only after about 33,000 years. However over the next few millennia the Orthodox calendar, like the Gregorian, will become increasingly inaccurate with respect to the mean solar year until possibly recovering around 10,000 years from now. However, in terms of the vernal equinox year the Gregorian Calendar is more accurate than the Orthodox and will remain more accurate in the coming millennia.

Those interested in pursuing this question further should consult (in addition to the articles linked in the previous paragraph) the following:

| L. E. Doggett | Calendars |

| Simon Cassidy | Implementing a correct 33-year calendar reform |

| Simon Cassidy | Re: How long is a year -- EXACTLY? |

| Duncan Steel | The Non-implemented 33-Year English Protestant Calendar |

| Astronomical Year Numbering and the Common Era Calendar | |

| Message Concerning Chronological Julian Days/Dates | |

| Calendar Studies | Date/Calendar Software |

| Hermetic Systems Home Page | |